The United States has been afflicted with a drug use epidemic for many years, which makes managing a narcotics investigation challenging.

Consider the current landscape: the past decade has focused particular attention on narcotics, including heroin, prescription opioids, and new synthetic opioids such as fentanyl and carfentanil. Opioid seizures has steadily increased from about 12,500 kilograms in 2017 to over 19,000 kilograms in 2021. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime found that seizures of cocaine in the U.S. rose from about 187,000 kilograms in 2019 to more than 251,000 in 2021. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, provisional data shows that over 100,000 Americans died from drug overdoses in the year ending 2022, while over 80,000 overdose deaths occurred in 2021 involving any opioid according to the National Institutes of Health. That latter statistic is generally attributed to the increased prevalence of fentanyl, which is more than 40 times stronger than heroin but didn’t even start showing up in the UN’s tallies until 2014. This epidemic doesn’t just ruin the lives of those who become addicted and the loved ones of those who die, it also destroys communities. According to Statista, in January 2022, more than 75% of U.S. adults agree that opioid abuse and addiction is a major problem.

The level of crime associated with narcotics trafficking makes neighborhoods dangerous and citizens frightened. Combating narcotics trafficking is a priority for law enforcement agencies, from both a public health and a community safety point of view.

Two Lines of Attack

The law enforcement effort happens at two levels. One targets the large organizations involved in trafficking—the importers, distributors, and so on. These investigations are multi-jurisdictional, involving multiple agencies coordinated at the county, state, and even federal levels. Local law enforcement may have a role, such as making undercover drug buys, but they don’t really have the resources to go after the entire organization on their own.

The other level is the effort to stop street-level dealing, which is where the issue of community safety comes in. A drug house can destroy the quality of life of an entire block or neighborhood. These are the kinds of narcotics trafficking investigations that local agencies are likely to be working on and can carry out by themselves. They tend to be “buy and bust” cases in which an undercover officer will make several purchases from the local storefront of an online drug delivery operation, leading to an arrest.

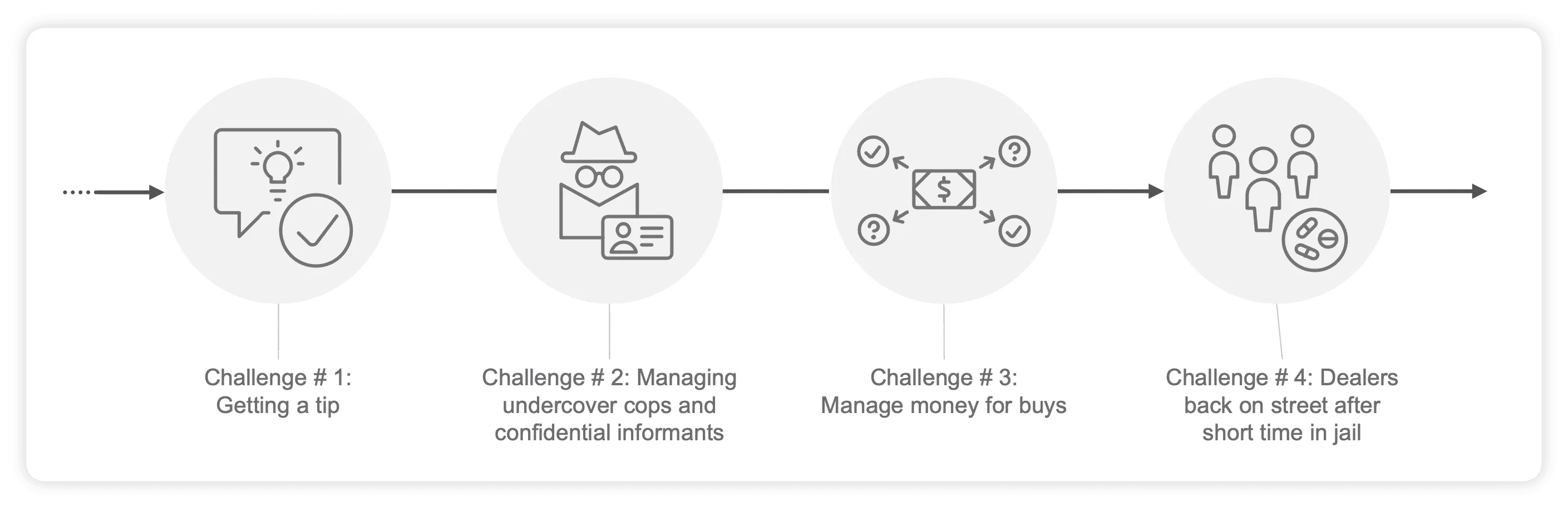

Challenges with Building a Narcotics Investigation

Such a local investigation usually starts with a tip. The tip will generally come from a citizen whose community is being disrupted by the street-level drug trade, but it can also come from a dissatisfied customer or even a competitor trying to damage the dealer’s business. After getting the tip, an investigator will make a series of observations to see if they can confirm its validity. If it’s confirmed, the next step is to assign an undercover officer to make buys. Each of these steps poses a challenge to investigators.

Challenge # 1: Getting a Tip

While the originating tip for a narcotics investigation may come from a dealer’s customers or competitors, affected citizens are the most likely to be motivated to make the call. However, they may also be understandably reluctant to inform authorities of a potentially dangerous criminal in their neighborhood.

Challenge # 2: Managing Undercover Cops and Confidential Informants

Once the observations are made and the agency decides the tip is worth following up on the next step is to arrange for a buy. That means establishing a fictitious identity for an undercover agent (or leveraging an existing one). The agent will work with a handler in the department, one of whose primary jobs is to protect the agent’s identity. They don’t work at the station house and won’t be known to the other cops; in fact, their role means they probably look like a criminal themselves. The in-house handler has to have a way of keeping track of the undercover’s activities without risking revealing their role.

Challenge # 3: Managing Money for Buys

Undercover agents also need funds to make the purchases that will lead to arrests, which is another important element to keep track of. Agencies can get into a lot of trouble if money goes missing and they can’t account for it. For one thing, undercover agents and CIs get robbed frequently, since they are, by definition, mixing with a criminal element. Also, sometimes planned buys just go wrong and the money is lost. It’s important for the agency to have the accountability that comes with documenting all financial transactions related to the investigation.

Challenge # 4: Dealers Back on the Street After Short Time in Jail

Even if a street-level dealer is arrested and convicted, they often don’t spend much time behind bars. They can be back on the street and back in business in a matter of months—certainly before the community has had a chance to fully recover. That means a challenge to a narcotics investigation is not simply to arrest or even convict the perpetrators, it’s also to change the public safety equation on the ground.

According to the National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics, arrests made for the sale and manufacture of heroin, cocaine, and derivative products have dropped over the last decade by 53%. Removing those responsible for supplying these drugs can have a substantial impact on outcomes.

How CaseBuilder™ and CrimeTracer™ Can Help

Take Tips through Portal

CaseBuilder includes a module that makes it easy for citizens to submit tips privately. The case management system has a tool for setting up a public-facing website that the agency can then link to from their home page or promote on social media. It allows the citizen to send information by filling out a submission form, and the information gets entered directly into the case management system.

Part of determining a tip’s validity is seeing if it fits into a pattern of suspicious activity. The CrimeTracer search tool plays a role here in enabling investigators to find past complaints involving the same address, drug-related arrests in the same area, and other data that could support the original tip.

Manage Confidentiality

CaseBuilder also has tools for restricting access to details about an investigation. An undercover agent’s handler can document the agent’s activity, record their drug buys, keep track of the expenditure and the products purchased, and even let the agent add comments. It all gets recorded in a highly confidential part of the system, and the agent is listed as just “undercover #27” or similar.

Manage Money for Buys

The investigators can also use CaseBuilder to pre-record the funds provided for drug buys. The handler can document all the bills with their serial numbers, establishing the paper trail necessary to provide accountability for any funds missing or spent.

Permanent change

Being able to build a solid case with CaseBuilder leads to the possibility of not just convicting dealers for their specific drug-related crimes, but also of providing the basis for civil actions to protect the community. Agencies can leverage nuisance abatement laws to trigger civil enforcement actions such as permanently locking a drug dealer’s storefront or even seeking asset forfeiture from the building owner if they were involved in the trafficking. To bring such a civil case, though, requires full documentation of all the steps that investigators did in breaking up the operation. That documentation is all within the CaseBuilder case file, along with the supporting data uncovered with CrimeTracer.

Conclusion

Bringing a narcotics trafficking investigation to a successful outcome requires the careful management of several interrelated elements, from the original tip that triggers the investigation through to the post-conviction actions that can keep the community safe after the specific case is over. These demands call for a flexible, comprehensive system like CaseBuilder, which puts all these tools on one platform.